North Pacific Gyre, or How the Great Pacific Garbage Patch was Formed

A couple weeks ago we looked at how objects from East Asia make their way to the Pacific Northwest Coast via the North Pacific Gyre, a system of ocean currents in the Pacific Ocean that rotate in a circular formation. Items that enter the gyre on one side can wash up on the other. However, not everything that enters the gyre makes it out. Many objects end up trapped in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

Garbage patches are formed when a significant amount of human debris become trapped in the center of a gyre. There are garbage patches in every major oceanic gyre on Earth, but the largest is the Great Pacific Garbage Patch (GPGP). While it is not possible to determine a definite size of the patch, estimates range from 270,000 to 5,800,000 square miles.

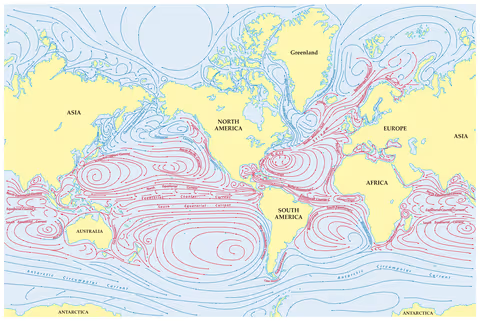

One of the factors that shape oceanic gyres are landmasses. Specifically, landmasses serve as boundaries for a gyre; as currents cannot continue on land, they are forced to run parallel to it or turn around. This is not limited to large landmasses like continents either. Islands can also have this effect.

As you can see on the map above, there are several surface currents that stem off of the Kuroshio, North Pacific, and California Currents and curl into the center of the gyre. These currents are then forced to turn back when they reach the Hawaiian Islands, which serve as a dividing point. As a result, the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is divided in two: the Eastern Garbage Patch between Hawaii and California and the Western Garbage Patch between Hawaii and Japan. They are connected by the North Pacific Subtropical Convergence Zone, which is located far enough north not to be affected by Hawaii.

The majority of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is composed of plastics. Because the waters in the center of a gyre are generally placid, plastic debris cannot escape and therefore break down into microplastics as they are exposed to the sun, wave activity, marine life, and temperature changes over time.

Microplastics are defined as plastics the size of a fingernail or smaller and as such not all microplastics can be seen with the naked eye or on satellite imagery. According to the Ocean Cleanup, microplastics make up the majority of the patch in terms of object count while larger plastics make up the majority in terms of mass.

Larger pieces of debris can make it out of a garbage patch or even circumvent one with a significant enough disturbance, such as a storm. After the 2011 Tōhoku Earthquake and Tsunami, a 2012 study discovered the tsunami had no significant impact on the Great Pacific Garbage Patch (CBC 2012). Another study predicted it would take several more years before the debris would impact the patch (TOS 2012)

Cleaning up the garbage patch is not a simple matter. Part of this is due to the size of microplastics making trawling difficult. Any nets small enough to catch microplastics will also catch most of the marine life in the area. It is also due in part to the sheer scale of the patch. The North Pacific Gyre encircles an area about 7.7 million square miles in size, meaning the patch occupies anywhere from 3.5% to 75% of this area. NOAA estimates it would take 67 ships one year to clean up less than one percent of the patch (2014).

On the individual level, the best thing we can do is help keep the patch from getting any larger by disposing of our garbage properly. So if you see a piece of plastic on the beach, pack it out and remember it is only a miniscule portion of what’s in the Pacific Ocean.

References

CBC News. (2012, August 09). Pacific ocean garbage mostly from home, not Japan Tsunami. Retrieved August 08, 2021, from https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/pacific-ocean-garbage-mostly-from-home-not-japan-tsunami-1.1278512

Evers, J. (Ed.). (2012, October 09). Great Pacific garbage patch. Retrieved July 16, 2021, from https://www.nationalgeographic.org/encyclopedia/great-pacific-garbage-patch/

Lebreton, L., Slat, B., Ferrari, F., Sainte-Rose, B., Aitken, J., Marthouse, R., . . . Reisser, J. (2018, March 22). Evidence that the Great Pacific garbage patch is rapidly Accumulating Plastic. Retrieved August 08, 2021, from https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-018-22939-w

The Ocean Cleanup. (2021, June 10). The great Pacific garbage patch. Retrieved August 07, 2021, from https://theoceancleanup.com/great-pacific-garbage-patch/

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. (2018, March 22). NOAA Ocean Podcast. Retrieved August 07, 2021, from https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/podcast/mar18/nop14-ocean-garbage-patches.html

Schiele. (n.d.). From your shopping cart to the ocean garbage patch impact. Retrieved August 08, 2021, from http://oceanmotion.org/html/impact/garbagepatch.htm

Bagulayan, A., J.N. Bartlett-Roa, A.L. Carter, B.G. Inman, E.M. Keen, E.C. Orenstein, N.V. Patin, K.N.S. Sato, E.C. Sibert, A.E. Simonis, A.M. Van Cise, and P.J.S. Franks. (2012). Journey to the center of the gyre: The fate of the Tohoku Tsunami debris field. Oceanography 25(2):200–207, https://doi.org/10.5670/oceanog.2012.55.

© Laura Caldwell, August 2021

Touch whale bones, examine shipwreck artifacts and connect with the coast's living history.

Support our mission, get involved in educational programs, or contribute through donations and volunteering.